Code

## End your R session programmatically

q()This chapter gives you the minimum essentials to start using R comfortably. It assumes no prior knowledge and emphasizes good habits from the very beginning. We cover how to start and quit R, get help, understand core object types, subset objects, use basic control structures, manage your working directory, and write clean code.

Rendering note. All code chunks use Quarto syntax and can be run via quarto render.

.R) or Quarto document (.qmd).Ctrl-Enter (Win/Linux) or Cmd-Enter (Mac). The console runs one complete line at a time.## End your R session programmatically

q()Positron is organized into panes and a sidebar.

.R and .qmd files; supports tabs.Ctrl-Shift-P or Cmd-Shift-P to search commands.Working in a project

data/ and scripts in R/ or src/.Running code

Ctrl/Cmd-Enter..qmd with the Run Cell button.Keep the Files and Console visible. Beginners benefit from constant feedback on where they are and what ran.

R has built‑in help for every function. Every call or command you type is calling a function.

Search the help system on a topic:

help.search("linear model")Get the documentation of a function with known name:

?mean

help(mean)Inspect arguments quickly for a function

args(mean)function (x, ...)

NULLRun examples in the documentation (man page)

example(mean)Practice: find how sd() handles missing values.

Everything you store is a vector or built from vectors. Length‑one values are still vectors.

Atomic vector types (all of fixed type):

## Atomic vectors (length one shown; still vectors)

num <- 3.14 ## double (numeric)

int <- 2L ## integer

chr <- "Ann" ## character

lgc <- TRUE ## logical

## A longer vector (same type throughout)

v <- c(1, 2, 3)Higher‑level structures built from vectors:

## Matrix/array: same type, 2D or more

m <- matrix(1:6, nrow = 2)

## List: heterogenous elements

lst <- list(name = "Bob", age = 25, scores = c(90, 88))

## Data frame: list of equal‑length columns

## (columns can be different atomic types)

df <- data.frame(name = c("Ann", "Bob"), age = c(20, 25))

## Function: also an object

sq <- function(x) x^2Inspect objects:

## Class and structure

class(df)[1] "data.frame"str(df)'data.frame': 2 obs. of 2 variables:

$ name: chr "Ann" "Bob"

$ age : num 20 25Prefer str(x) for a compact view of what an object contains, its type, and its sizes.

Exercise. Create one example of each object above and check with class() and str().

Use bracket notation consistently.

## Vectors

x <- c(2, 4, 6, 8)

x[2] ## second element[1] 4x[1:3] ## slice[1] 2 4 6x[x > 5] ## logical filter[1] 6 8## Matrices

m <- matrix(1:9, nrow = 3)

m[2, 3] ## row 2, col 3[1] 8m[, 1] ## first column[1] 1 2 3## Data frames

people <- data.frame(name = c("Ann", "Bob"), age = c(20, 25))

people$age ## column by name[1] 20 25people[1, ] ## first rowpeople[, "name"] ## column by string[1] "Ann" "Bob"## Replace sentinel values with NA

x <- -999

if (x == -999) {

x <- NA

}

print(x)[1] NAUseful when applying a simple rule across columns.

## Make a toy data frame with a sentinel value

scores <- data.frame(

math = c(95, -999, 88, 91),

eng = c(87, 90, -999, 85),

sci = c(92, 88, 94, -999)

)

## Replace -999 with NA, then compute column means

for (col in names(scores)) {

## clean

bad <- scores[[col]] == -999

scores[[col]][bad] <- NA

## summarize

m <- mean(scores[[col]], na.rm = TRUE)

cat(col, "mean:", m, "\n")

}math mean: 91.33333

eng mean: 87.33333

sci mean: 91.33333 Stop when an estimate is precise enough.

## Estimate P(X > 1.96) for N(0,1) via Monte Carlo

## Stop when stderr < 0.002

set.seed(1)

count <- 0

n <- 0

se <- Inf

while (se > 0.002) {

## simulate in small batches for responsiveness

z <- rnorm(1000)

n <- n + length(z)

count <- count + sum(z > 1.96)

p_hat <- count / n

se <- sqrt(p_hat * (1 - p_hat) / n)

}

cat("p_hat:", p_hat, "n:", n, "se:", se, "\n")p_hat: 0.0285 n: 8000 se: 0.001860368 Exercise. Write a loop that, for each numeric column in a frame, replaces -999 with NA, then reports the fraction of missing values.

Loops are fine for clarity. Later you will see vectorized and apply‑family solutions that are faster and shorter.

## Working directory

getwd() ## where am I[1] "/Users/junyan/work/teaching/1010-f25/1010f25"## setwd("path/to/folder") ## set if necessary.qmd.Ctrl/Cmd-Enter.Use project‑relative paths and file.path() to build paths. This keeps code portable across operating systems.

R can load data from text files and many other formats.

## Read a CSV file (comma-separated)

cars <- read.csv("data/india.csv")

## Read a general table with custom separators

survey <- read.table("data/survey.txt", header = TRUE, sep = " ")Arguments to know: - header = TRUE tells R the first row has column names. - sep controls the separator (“,” for CSV, ” ” for tab‑delimited).

Check the imported object with str() or head() immediately to ensure it loaded as expected.

The foreign package imports legacy statistical software formats (SAS, SPSS, Stata):

library(foreign)

data_spss <- read.spss("data/study.sav", to.data.frame = TRUE)

data_stata <- read.dta("data/study.dta")More modern workflows often use the haven package (part of the tidyverse) for these formats, but foreign is available in base R distributions.

Adopt consistent style early. Follow the tidyverse guide: https://style.tidyverse.org/

<- for assignment.## Your Name

## 2025-09-02

## Purpose: demonstrate basic R style

x <- 1 # inline note uses a single Comment convention. Start‑of‑line comments use at least two hashes (##). Reserve a single # for end‑of‑line notes.

x and X are different./ work on all platforms in R.## Portable path building

file.path("data", "mtcars.csv")[1] "data/mtcars.csv"## Floating‑point comparison

0.1 == 0.3 / 3[1] FALSEall.equal(0.1, 0.3 / 3)[1] TRUE## Reveal stored value with extra digits

print(0.1, digits = 20)[1] 0.10000000000000000555sprintf("%.17f", 0.1)[1] "0.10000000000000001"Use all.equal() (or an absolute/relative tolerance) rather than == for real‑number comparisons.

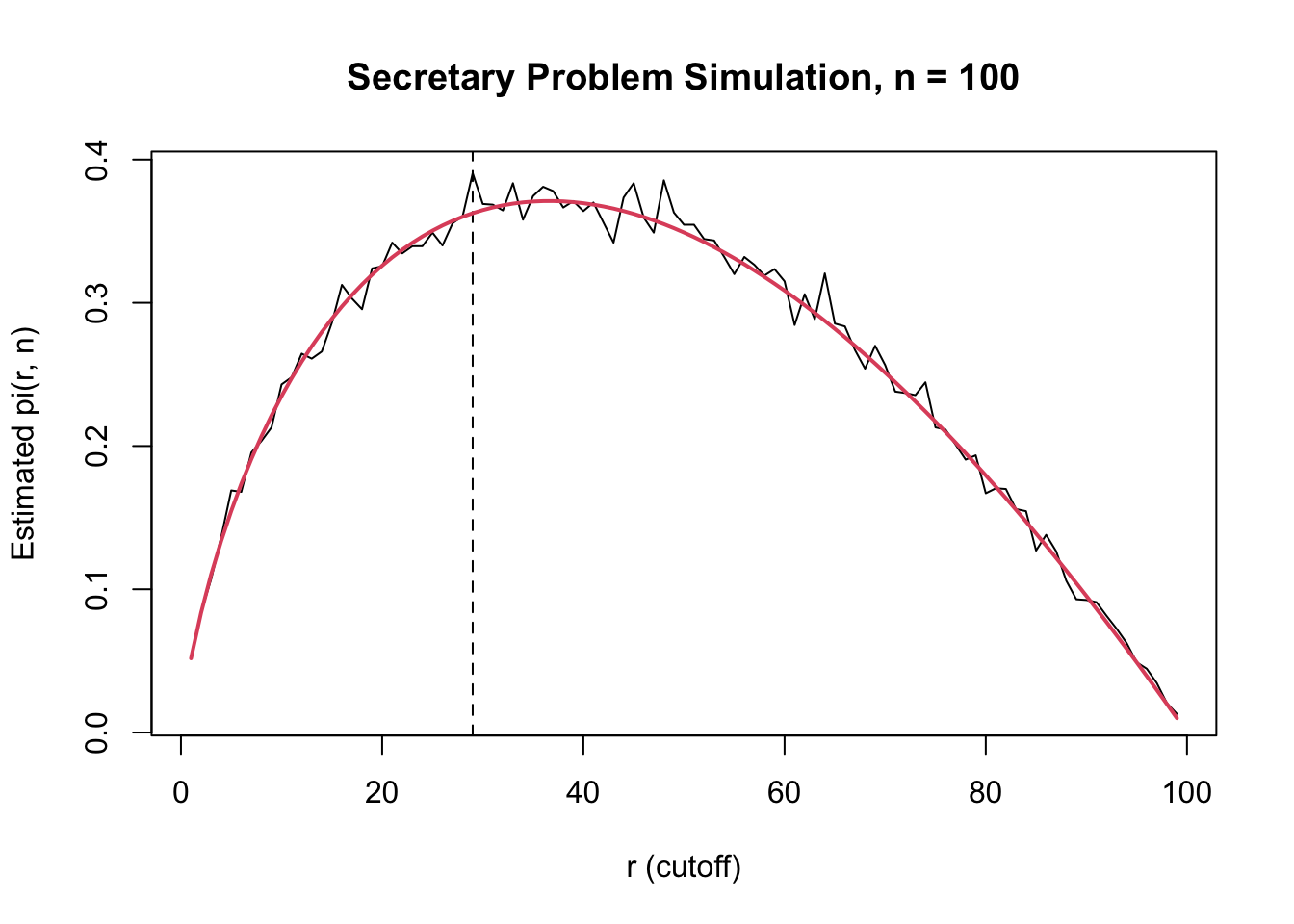

A manager wants to hire one secretary from among \(n\) applicants. According to some standard, the applicants can be strictly ranked from strongest to weakest, but the order in which they are interviewed is completely random. For each interview the manager must immediately decide whether to hire this person. If the applicant is hired, the process stops. Otherwise the manager moves on to the next applicant. Any rejected applicant cannot be recalled later. What rule should the manager use in order to maximize the probability that the person hired is actually the best of the \(n\) applicants?

Consider the following strategy. Choose an integer \(r < n\). The manager first interviews the first \(r\) applicants and rejects all of them. Then, starting from applicant \(r+1\), the manager hires the first applicant whose quality is better than all previous applicants. If no such applicant appears, the manager hires the last applicant.

Let \(\pi(r,n)\) be the probability that this strategy results in hiring the best applicant. It can be shown that

\[ \begin{aligned} \pi(r,n) &= \sum_{i=1}^{n} \Pr(\text{strongest in first } i-1 \text{ is in } 1,\dots,r)\, \Pr(\text{strongest at position } i) \\ &= \sum_{i=r+1}^{n} \frac{r}{i-1}\cdot \frac{1}{n}. \end{aligned} \]

The problem is to choose \(r\) to maximize \(\pi(r,n)\).

Now we estimate the probability \(\pi(r,n)\) of selecting the best candidate in the classical secretary problem using simulation in R. For each candidate number \(n\) and cutoff \(r\), we simulate the hiring process repeatedly and compute the proportion of simulations in which the selected applicant is the best (rank \(1\)).

We represent the applicants’ true qualities as a random permutation of \(\{1,\dots,n\}\), where \(1\) is best and \(n\) is worst. With a given cutoff \(r\), we first examine the first \(r\) applicants and record the smallest (rank-best) value among them. Starting from applicant \(r+1\), we hire the first applicant whose rank is smaller than all previously observed ranks. If none is better, we hire the last applicant.

secretary_once <- function(n, r) {

# A random permutation of ranks, where 1 = best

order <- sample.int(n)

# Best rank seen among the first r applicants

best_so_far <- min(order[1:r])

# Default: hire the last applicant

hire_index <- n

# Look for the first applicant better than all previous ones

if (r < n) {

for (i in (r + 1):n) {

if (order[i] < best_so_far) {

hire_index <- i

break

}

}

}

hired_rank <- order[hire_index]

as.integer(hired_rank == 1)

}We repeat the random hiring process many times and compute the average success probability.

estimate_pi <- function(n, r, n_sim = 10000) {

mean(replicate(n_sim, secretary_once(n, r)))

}For a fixed \(n\), we evaluate \(\pi(r,n)\) over \(r = 1, \dots, n-1\) and select the \(r\) that maximizes the probability of hiring the best applicant.

n <- 100

n_sim <- 2000

rs <- 1:(n - 1)

pis <- sapply(rs, estimate_pi, n = n, n_sim = n_sim)

r_star_hat <- rs[which.max(pis)]

max_prob_hat <- max(pis)

r_star_hat[1] 29max_prob_hat[1] 0.3905We can visualize the function \(r \mapsto \pi(r,n)\):

plot(rs, pis, type = "l",

xlab = "r (cutoff)",

ylab = "Estimated pi(r, n)",

main = paste("Secretary Problem Simulation, n =", n))

abline(v = r_star_hat, lty = 2)

lines(rs, sapply(rs, function(r) sum((r)/((r+1):100 - 1)) / 100), col = 2, lwd = 2)

As \(n \to \infty\), \(r^* / n \to 1 / e \approx 0.368\).

You should now be able to:

class() and str().if, for, and while in useful contexts.