import pandas as pd6 Data Manipulation

6.1 Introduction

Data manipulation is crucial for transforming raw data into a more analyzable format, essential for uncovering patterns and ensuring accurate analysis. This chapter introduces the core techniques for data manipulation in Python, utilizing the Pandas library, a cornerstone for data handling within Python’s data science toolkit.

Python’s ecosystem is rich with libraries that facilitate not just data manipulation but comprehensive data analysis. Pandas, in particular, provides extensive functionality for data manipulation tasks including reading, cleaning, transforming, and summarizing data. Using real-world datasets, we will explore how to leverage Python for practical data manipulation tasks.

By the end of this chapter, you will learn to:

- Import/export data from/to diverse sources.

- Clean and preprocess data efficiently.

- Transform and aggregate data to derive insights.

- Merge and concatenate datasets from various origins.

- Analyze real-world datasets using these techniques.

6.2 Data Manipulation with Pandas

This section was written by Owen Sgro.

6.2.1 Introduction

My name is Owen Sgro and I’m a Statistical Data Science major, minoring in Computer Science. I’ll be talking about Data Manipulation using Pandas. For this presentation I’ll be using the NYC Crash Data we cleaned.

6.2.1.1 What is Pandas?

- Pandas is the primary Python library for data manipulation and analysis

- It provides tools to load, clean, filter, transform, and summarize datasets.

6.2.1.2 Why Use Pandas?

- Intuitive table-like structure (similar to R’s data frames)

- Handles missing data

- Built-in methods for grouping, filtering, merging, and reshaping

- Works seamlessly with libraries like Plotnine, Matplotlib , and NumPy

6.2.2 Getting Started

6.2.2.1 Importing Pandas

- For our examples we will use the cleaned feather of the NYC crash data (courtesy of Wilson Tang)

- Feather files are fast, binary formats for data, perfect for usage with Pandas.

- pip install pandas

6.2.2.2 Reading Data

# Load dataset

df = pd.read_feather("data/nyc_crashes_cleaned.feather")

df.head()| borough | zip_code | latitude | longitude | on_street_name | cross_street_name | off_street_name | number_of_persons_injured | number_of_persons_killed | number_of_pedestrians_injured | ... | collision_id | vehicle_type_code_1 | vehicle_type_code_2 | vehicle_type_code_3 | vehicle_type_code_4 | vehicle_type_code_5 | was_fillable | zip_code_numeric | zip_filled | crash_datetime | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | QUEENS | 11101 | 40.753113 | -73.933701 | 30 ST | 39 AVE | None | 0 | 1 | 0 | ... | 4838875 | Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle | None | None | None | None | False | 11101.0 | False | 2025-08-31 12:49:00 |

| 1 | MANHATTAN | 10022 | 40.760601 | -73.964317 | E 59 ST | 2 AVE | None | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 4839110 | Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle | None | None | None | None | False | 10022.0 | False | 2025-08-31 15:30:00 |

| 2 | None | 11040 | 40.734234 | -73.722748 | CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY | HILLSIDE AVENUE | None | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 4838966 | Sedan | Sedan | None | None | None | True | 11040.0 | True | 2025-08-31 19:00:00 |

| 3 | BROOKLYN | 11220 | 40.648075 | -74.007034 | None | None | 4415 5 AVE | 2 | 0 | 0 | ... | 4838563 | Sedan | E-Bike | None | None | None | False | 11220.0 | False | 2025-08-31 01:19:00 |

| 4 | MANHATTAN | 10036 | 40.756561 | -73.986107 | W 43 ST | BROADWAY | None | 1 | 0 | 0 | ... | 4838922 | Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle | Bike | None | None | None | False | 10036.0 | False | 2025-08-31 02:41:00 |

5 rows × 30 columns

6.2.3 Exploring Data

- info() –> column types and missing values

df.info()<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 1381 entries, 0 to 1380

Data columns (total 30 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 borough 1367 non-null object

1 zip_code 1365 non-null object

2 latitude 1345 non-null float32

3 longitude 1345 non-null float32

4 on_street_name 953 non-null object

5 cross_street_name 839 non-null object

6 off_street_name 428 non-null object

7 number_of_persons_injured 1381 non-null int64

8 number_of_persons_killed 1381 non-null int64

9 number_of_pedestrians_injured 1381 non-null int64

10 number_of_pedestrians_killed 1381 non-null int64

11 number_of_cyclist_injured 1381 non-null int64

12 number_of_cyclist_killed 1381 non-null int64

13 number_of_motorist_injured 1381 non-null int64

14 number_of_motorist_killed 1381 non-null int64

15 contributing_factor_vehicle_1 1372 non-null object

16 contributing_factor_vehicle_2 1059 non-null object

17 contributing_factor_vehicle_3 118 non-null object

18 contributing_factor_vehicle_4 33 non-null object

19 contributing_factor_vehicle_5 12 non-null object

20 collision_id 1381 non-null int64

21 vehicle_type_code_1 1364 non-null object

22 vehicle_type_code_2 945 non-null object

23 vehicle_type_code_3 112 non-null object

24 vehicle_type_code_4 30 non-null object

25 vehicle_type_code_5 12 non-null object

26 was_fillable 1381 non-null bool

27 zip_code_numeric 1365 non-null float64

28 zip_filled 1381 non-null bool

29 crash_datetime 1381 non-null datetime64[ns]

dtypes: bool(2), datetime64[ns](1), float32(2), float64(1), int64(9), object(15)

memory usage: 304.8+ KB- describe() –> summary statistics for numeric columns

df.describe()| latitude | longitude | number_of_persons_injured | number_of_persons_killed | number_of_pedestrians_injured | number_of_pedestrians_killed | number_of_cyclist_injured | number_of_cyclist_killed | number_of_motorist_injured | number_of_motorist_killed | collision_id | zip_code_numeric | crash_datetime | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 1345.000000 | 1345.000000 | 1381.000000 | 1381.000000 | 1381.000000 | 1381.000000 | 1381.000000 | 1381.0 | 1381.000000 | 1381.000000 | 1.381000e+03 | 1365.000000 | 1381 |

| mean | 40.715656 | -73.914635 | 0.663287 | 0.004345 | 0.099203 | 0.000724 | 0.070963 | 0.0 | 0.473570 | 0.003621 | 4.839709e+06 | 10919.303297 | 2025-09-03 08:55:21.853729024 |

| min | 40.507755 | -74.243088 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 4.838563e+06 | 10001.000000 | 2025-08-31 00:00:00 |

| 25% | 40.657665 | -73.969521 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 4.839274e+06 | 10457.000000 | 2025-09-01 17:05:00 |

| 50% | 40.708607 | -73.921539 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 4.839714e+06 | 11212.000000 | 2025-09-03 08:00:00 |

| 75% | 40.765766 | -73.860085 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 4.840132e+06 | 11354.000000 | 2025-09-05 00:23:00 |

| max | 40.897251 | -73.711029 | 10.000000 | 2.000000 | 4.000000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 0.0 | 10.000000 | 2.000000 | 4.840663e+06 | 11694.000000 | 2025-09-06 23:33:00 |

| std | 0.080481 | 0.087819 | 0.935774 | 0.076015 | 0.324606 | 0.026909 | 0.265185 | 0.0 | 0.926379 | 0.071129 | 5.286559e+02 | 524.076952 | NaN |

6.2.4 Selecting and Filtering Data

We can select the rows that we want included in the data.

df["borough"].head()

df[["borough", "crash_datetime", "number_of_persons_injured"]].head()| borough | crash_datetime | number_of_persons_injured | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | QUEENS | 2025-08-31 12:49:00 | 0 |

| 1 | MANHATTAN | 2025-08-31 15:30:00 | 0 |

| 2 | None | 2025-08-31 19:00:00 | 0 |

| 3 | BROOKLYN | 2025-08-31 01:19:00 | 2 |

| 4 | MANHATTAN | 2025-08-31 02:41:00 | 1 |

In this next text block we filter the data by number_of_persons_injured.

injured = df[df["number_of_persons_injured"] > 0]

print(injured.head(5)) borough zip_code latitude longitude on_street_name cross_street_name \

3 BROOKLYN 11220 40.648075 -74.007034 None None

4 MANHATTAN 10036 40.756561 -73.986107 W 43 ST BROADWAY

5 BRONX 10466 40.887672 -73.847046 LACONIA AVE GRENADA PL

9 QUEENS 11004 40.736752 -73.711029 HILLSIDE AVE 257 ST

10 MANHATTAN 10002 40.714314 -73.987167 E BROADWAY CLINTON ST

off_street_name number_of_persons_injured number_of_persons_killed \

3 4415 5 AVE 2 0

4 None 1 0

5 None 1 0

9 None 1 0

10 None 1 0

number_of_pedestrians_injured ... collision_id \

3 0 ... 4838563

4 0 ... 4838922

5 1 ... 4839184

9 0 ... 4838641

10 1 ... 4838841

vehicle_type_code_1 vehicle_type_code_2 \

3 Sedan E-Bike

4 Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle Bike

5 None None

9 Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle Sedan

10 Sedan None

vehicle_type_code_3 vehicle_type_code_4 vehicle_type_code_5 was_fillable \

3 None None None False

4 None None None False

5 None None None False

9 None None None False

10 None None None False

zip_code_numeric zip_filled crash_datetime

3 11220.0 False 2025-08-31 01:19:00

4 10036.0 False 2025-08-31 02:41:00

5 10466.0 False 2025-08-31 19:42:00

9 11004.0 False 2025-08-31 10:25:00

10 10002.0 False 2025-08-31 17:53:00

[5 rows x 30 columns]6.2.5 Using Boolean and .loc

.locis used to access groups of rows and columns by labels or Boolean conditions.

# Select first 5 rows and specific columns

df.loc[0:5, ["borough", "number_of_persons_injured"]]| borough | number_of_persons_injured | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | QUEENS | 0 |

| 1 | MANHATTAN | 0 |

| 2 | None | 0 |

| 3 | BROOKLYN | 2 |

| 4 | MANHATTAN | 1 |

| 5 | BRONX | 1 |

6.2.6 DataFrame, Series, and Selecting Columns

DataFrame

- 2D labeled data structure

- Like a table in Excel

- Each column is a Series

- df.head() is how you view the first few rows

Series

- One-dimensional labeled array

- Can hold any data type: integers, floats, strings, etc.

# Selecting a Series

df["borough"].head()

# Accessing Series Properties

df["borough"].dtype # Data type

df["borough"].nunique() # Number of unique values

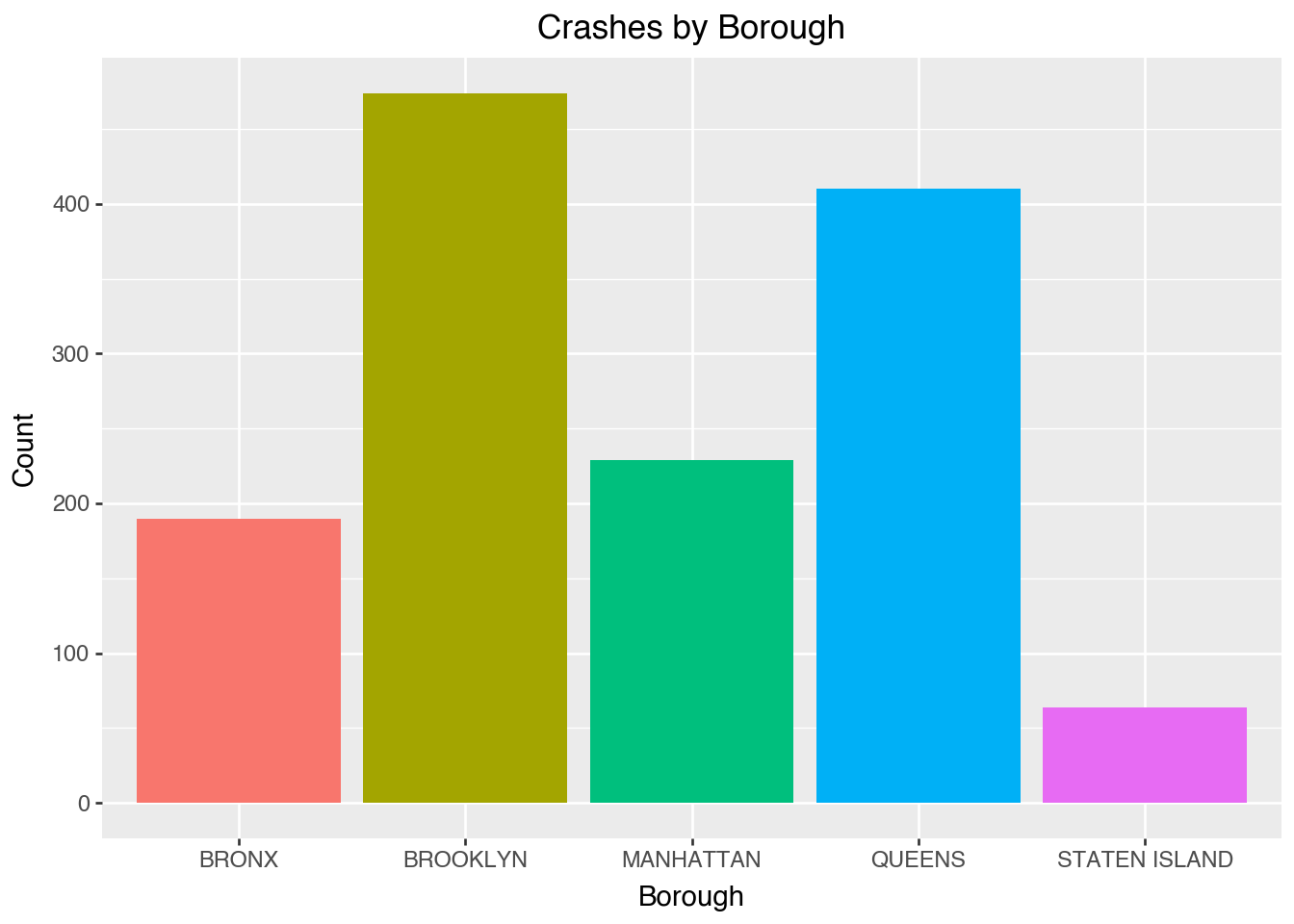

df["borough"].value_counts().head() # Frequency of top categoriesborough

BROOKLYN 474

QUEENS 410

MANHATTAN 229

BRONX 190

STATEN ISLAND 64

Name: count, dtype: int64Selecting Columns

- Selecting one column returns a Series, selecting multiple returns a DataFrame

df["borough"].head()

df[["borough", "crash_datetime", "number_of_persons_injured"]].head()| borough | crash_datetime | number_of_persons_injured | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | QUEENS | 2025-08-31 12:49:00 | 0 |

| 1 | MANHATTAN | 2025-08-31 15:30:00 | 0 |

| 2 | None | 2025-08-31 19:00:00 | 0 |

| 3 | BROOKLYN | 2025-08-31 01:19:00 | 2 |

| 4 | MANHATTAN | 2025-08-31 02:41:00 | 1 |

6.2.7 Transforming Data

Here we extract crash hour from datetime, then create a severity label using a custom rule.

# Extract crash hour from datetime

df["hour"] = df["crash_datetime"].dt.hour

# Create severity label using a custom rule

df["severity"] = df["number_of_persons_injured"].apply(

lambda x: "Severe" if x > 2 else "Minor"

)

df[["borough", "hour", "severity"]].head()| borough | hour | severity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | QUEENS | 12 | Minor |

| 1 | MANHATTAN | 15 | Minor |

| 2 | None | 19 | Minor |

| 3 | BROOKLYN | 1 | Minor |

| 4 | MANHATTAN | 2 | Minor |

- In Pandas you can:

- convert text to uppercase

- create a binary flag column

- rename columns for consistency

# Convert text to uppercase

df["borough"] = df["borough"].str.upper()

# Create a binary flag column

df["injury_flag"] = (df["number_of_persons_injured"] > 0).astype(int)

# Rename columns for consistency

df = df.rename(columns={"number_of_persons_injured": "persons_injured"})

print(df[["borough", "injury_flag"]].head(5)) borough injury_flag

0 QUEENS 0

1 MANHATTAN 0

2 None 0

3 BROOKLYN 1

4 MANHATTAN 16.2.8 Dealing with Missing Data

- Pandas has flexible options for dropping, filling, or interpolating missing data.

Here we can check the missing values and drop missing entries.

# Check missing values per column

df.isna().sum()

# Drop missing borough entries

df = df.dropna(subset=["borough"])- Fill with a default value

- Forward or backward fill (useful for time-series)

- Replace missing numberic data with mean or median

- Check proportion of missingness

# Fill missing categorical values

df["borough"] = df["borough"].fillna("Unknown")

# Forward fill numberic columns

df["persons_injured"] = df["persons_injured"].ffill()

# Fill missing 'hour' with mean

df["hour"].fillna(df["hour"].mean(), inplace=True)

# Percentage of missing values

df.isna().mean() * 100/var/folders/cq/5ysgnwfn7c3g0h46xyzvpj800000gn/T/ipykernel_8921/3700694978.py:8: FutureWarning:

A value is trying to be set on a copy of a DataFrame or Series through chained assignment using an inplace method.

The behavior will change in pandas 3.0. This inplace method will never work because the intermediate object on which we are setting values always behaves as a copy.

For example, when doing 'df[col].method(value, inplace=True)', try using 'df.method({col: value}, inplace=True)' or df[col] = df[col].method(value) instead, to perform the operation inplace on the original object.

borough 0.000000

zip_code 0.365764

latitude 1.828822

longitude 1.828822

on_street_name 31.236284

cross_street_name 39.209949

off_street_name 68.763716

persons_injured 0.000000

number_of_persons_killed 0.000000

number_of_pedestrians_injured 0.000000

number_of_pedestrians_killed 0.000000

number_of_cyclist_injured 0.000000

number_of_cyclist_killed 0.000000

number_of_motorist_injured 0.000000

number_of_motorist_killed 0.000000

contributing_factor_vehicle_1 0.658376

contributing_factor_vehicle_2 23.335772

contributing_factor_vehicle_3 91.587418

contributing_factor_vehicle_4 97.732260

contributing_factor_vehicle_5 99.122165

collision_id 0.000000

vehicle_type_code_1 1.243599

vehicle_type_code_2 31.602048

vehicle_type_code_3 91.953182

vehicle_type_code_4 97.951719

vehicle_type_code_5 99.122165

was_fillable 0.000000

zip_code_numeric 0.365764

zip_filled 0.000000

crash_datetime 0.000000

hour 0.000000

severity 0.000000

injury_flag 0.000000

dtype: float646.2.9 Summarizing Data

- We can compute the average number of injuries per crash by borough:

# Average injuries per crash by borough

df.groupby("borough")["persons_injured"].mean().sort_values(ascending=False)borough

BRONX 0.800000

BROOKLYN 0.664557

QUEENS 0.634146

MANHATTAN 0.620087

STATEN ISLAND 0.562500

Name: persons_injured, dtype: float64- Groupby can also perform multiple summary statistics at once

df.groupby("borough")["persons_injured"].agg(["mean", "max", "count"])| mean | max | count | |

|---|---|---|---|

| borough | |||

| BRONX | 0.800000 | 6 | 190 |

| BROOKLYN | 0.664557 | 10 | 474 |

| MANHATTAN | 0.620087 | 7 | 229 |

| QUEENS | 0.634146 | 8 | 410 |

| STATEN ISLAND | 0.562500 | 3 | 64 |

- We have two ways to count crashes:

df["borough"].value_counts()

# OR equivalently:

df.groupby("borough").size().reset_index(name="crash_count")| borough | crash_count | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | BRONX | 190 |

| 1 | BROOKLYN | 474 |

| 2 | MANHATTAN | 229 |

| 3 | QUEENS | 410 |

| 4 | STATEN ISLAND | 64 |

- Pivot tables are great for reshaping summaries

pivot = pd.pivot_table(

df,

values="persons_injured",

index="borough",

columns="hour",

aggfunc="mean"

)

# Round for readability

pivot_rounded = pivot.round(2)

# Slice for hours 1 to 5

pivot_rounded_subset = pivot_rounded.loc[:, 1:5]- We can output a pivot table of, average injuries per hour by Borough (hours 1-5)

| hour | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| borough | |||||

| BRONX | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 2.00 | 0.67 |

| BROOKLYN | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.36 |

| MANHATTAN | 0.33 | 0.67 | 1.80 | 0.33 | 0.55 |

| QUEENS | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.83 |

| STATEN ISLAND | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0.00 |

6.2.10 Combining and Visualizing Data

We can merge our borough data with the populatio data of those boroughs.

borough_pop = pd.DataFrame({

"borough": ["Bronx", "Brooklyn", "Manhattan", "Queens", "Staten Island"],

"population": [1472654, 2559903, 1628706, 2253858, 487155]

})

merged = pd.merge(df, borough_pop, on="borough", how="inner")- Real-world data often needs to be restructured for analysis or visualization

- Pandas provides powerful tools to switch between wide and long formats

Here we can convert our data from wide to long format.

# Convert from wide to long format

long_df = pd.melt(

df,

id_vars=["borough", "hour"],

value_vars=["persons_injured"],

var_name="metric",

value_name="value"

)

long_df.head()

# Export to CSV

import os

os.makedirs("output", exist_ok=True)

long_df.to_csv("output/nyc_crash_long.csv", index=False)6.2.11 Visualizing with Plotnine

We can visualize data in Pandas with plotnine. - We can see that Brooklyn and Queens typically have higher crash counts - Reflects both population and traffic density

from plotnine import *

(ggplot(df, aes(x="borough", fill="borough"))

+ geom_bar(show_legend=False)

+ labs(title="Crashes by Borough", x="Borough", y="Count"))

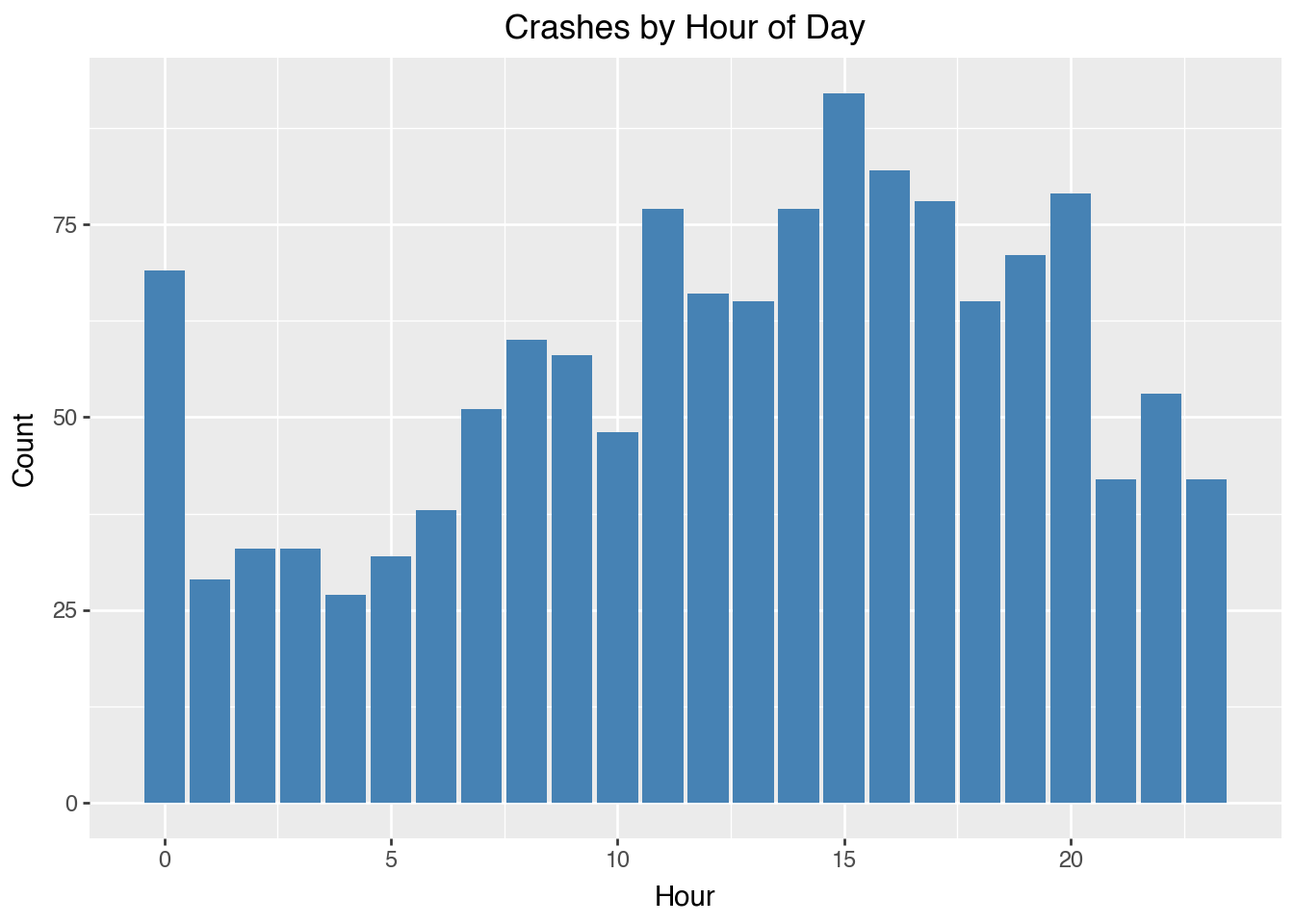

Here we calculate the crash frequency per hour. - Crash frequency tends to increase during commute hours (rush hour)

(ggplot(df, aes(x="hour"))

+ geom_bar(fill="steelblue")

+ labs(title="Crashes by Hour of Day", x="Hour", y="Count"))

6.2.12 Wrapping Up

- Pandas simplifies all stages of data analysis.

- Exploration (head(), info(), describe())

- Cleaning and Transformation (apply(), dropna())

- Summarization (groupby(), pivot_table())

- Combination and Reshaping (merge(), melt())

- Integrates seamlessly with NumPy and Plotnine

- Enables reproducible, efficient, and scalable data workflows

- Mastering Pandas provides a strong foundation for machine learning, visualization, and statistical modeling

6.2.13 Resources

6.3 Example: NYC Crash Data

Consider a subset of the NYC Crash Data, which contains all NYC motor vehicle collisions data with documentation from NYC Open Data. We downloaded the crash data for the week of August 31, 2025, on September 11, 2025, in CSC format.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# Load the dataset

file_path = 'data/nyc_crashes_lbdwk_2025.csv'

df = pd.read_csv(file_path,

dtype={'LATITUDE': np.float32,

'LONGITUDE': np.float32,

'ZIP CODE': str})

# Replace column names: convert to lowercase and replace spaces with underscores

df.columns = df.columns.str.lower().str.replace(' ', '_')

# Check for missing values

df.isnull().sum()crash_date 0

crash_time 0

borough 284

zip_code 284

latitude 12

longitude 12

location 12

on_street_name 456

cross_street_name 587

off_street_name 1031

number_of_persons_injured 0

number_of_persons_killed 0

number_of_pedestrians_injured 0

number_of_pedestrians_killed 0

number_of_cyclist_injured 0

number_of_cyclist_killed 0

number_of_motorist_injured 0

number_of_motorist_killed 0

contributing_factor_vehicle_1 9

contributing_factor_vehicle_2 355

contributing_factor_vehicle_3 1358

contributing_factor_vehicle_4 1447

contributing_factor_vehicle_5 1474

collision_id 0

vehicle_type_code_1 17

vehicle_type_code_2 475

vehicle_type_code_3 1363

vehicle_type_code_4 1452

vehicle_type_code_5 1474

dtype: int64Take a peek at the first five rows:

df.head()| crash_date | crash_time | borough | zip_code | latitude | longitude | location | on_street_name | cross_street_name | off_street_name | ... | contributing_factor_vehicle_2 | contributing_factor_vehicle_3 | contributing_factor_vehicle_4 | contributing_factor_vehicle_5 | collision_id | vehicle_type_code_1 | vehicle_type_code_2 | vehicle_type_code_3 | vehicle_type_code_4 | vehicle_type_code_5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 08/31/2025 | 12:49 | QUEENS | 11101 | 40.753113 | -73.933701 | (40.753113, -73.9337) | 30 ST | 39 AVE | NaN | ... | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 4838875 | Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 1 | 08/31/2025 | 15:30 | MANHATTAN | 10022 | 40.760601 | -73.964317 | (40.7606, -73.96432) | E 59 ST | 2 AVE | NaN | ... | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 4839110 | Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 2 | 08/31/2025 | 19:00 | NaN | NaN | 40.734234 | -73.722748 | (40.734234, -73.72275) | CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY | HILLSIDE AVENUE | NaN | ... | Unspecified | Unspecified | NaN | NaN | 4838966 | Sedan | Sedan | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 3 | 08/31/2025 | 1:19 | BROOKLYN | 11220 | 40.648075 | -74.007034 | (40.648075, -74.007034) | NaN | NaN | 4415 5 AVE | ... | Unspecified | NaN | NaN | NaN | 4838563 | Sedan | E-Bike | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 4 | 08/31/2025 | 2:41 | MANHATTAN | 10036 | 40.756561 | -73.986107 | (40.75656, -73.98611) | W 43 ST | BROADWAY | NaN | ... | Unspecified | NaN | NaN | NaN | 4838922 | Station Wagon/Sport Utility Vehicle | Bike | NaN | NaN | NaN |

5 rows × 29 columns

A quick summary of the data types of the columns:

df.info()<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 1487 entries, 0 to 1486

Data columns (total 29 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 crash_date 1487 non-null object

1 crash_time 1487 non-null object

2 borough 1203 non-null object

3 zip_code 1203 non-null object

4 latitude 1475 non-null float32

5 longitude 1475 non-null float32

6 location 1475 non-null object

7 on_street_name 1031 non-null object

8 cross_street_name 900 non-null object

9 off_street_name 456 non-null object

10 number_of_persons_injured 1487 non-null int64

11 number_of_persons_killed 1487 non-null int64

12 number_of_pedestrians_injured 1487 non-null int64

13 number_of_pedestrians_killed 1487 non-null int64

14 number_of_cyclist_injured 1487 non-null int64

15 number_of_cyclist_killed 1487 non-null int64

16 number_of_motorist_injured 1487 non-null int64

17 number_of_motorist_killed 1487 non-null int64

18 contributing_factor_vehicle_1 1478 non-null object

19 contributing_factor_vehicle_2 1132 non-null object

20 contributing_factor_vehicle_3 129 non-null object

21 contributing_factor_vehicle_4 40 non-null object

22 contributing_factor_vehicle_5 13 non-null object

23 collision_id 1487 non-null int64

24 vehicle_type_code_1 1470 non-null object

25 vehicle_type_code_2 1012 non-null object

26 vehicle_type_code_3 124 non-null object

27 vehicle_type_code_4 35 non-null object

28 vehicle_type_code_5 13 non-null object

dtypes: float32(2), int64(9), object(18)

memory usage: 325.4+ KBNow we can do some cleaning after a quick browse.

# Replace invalid coordinates (latitude=0, longitude=0 or NaN) with NaN

df.loc[(df['latitude'] == 0) & (df['longitude'] == 0),

['latitude', 'longitude']] = pd.NA

df['latitude'] = df['latitude'].replace(0, pd.NA)

df['longitude'] = df['longitude'].replace(0, pd.NA)

# Drop the redundant `latitute` and `longitude` columns

df = df.drop(columns=['location'])

# Converting 'crash_date' and 'crash_time' columns into a single datetime column

df['crash_datetime'] = pd.to_datetime(df['crash_date'] + ' '

+ df['crash_time'], format='%m/%d/%Y %H:%M', errors='coerce')

# Drop the original 'crash_date' and 'crash_time' columns

df = df.drop(columns=['crash_date', 'crash_time'])Let’s get some basic frequency tables of borough and zip_code, whose values could be used to check their validity against the legitmate values.

# Frequency table for 'borough' without filling missing values

borough_freq = df['borough'].value_counts(dropna=False).reset_index()

borough_freq.columns = ['borough', 'count']

# Frequency table for 'zip_code' without filling missing values

zip_code_freq = df['zip_code'].value_counts(dropna=False).reset_index()

zip_code_freq.columns = ['zip_code', 'count']

zip_code_freq| zip_code | count | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | NaN | 284 |

| 1 | 11207 | 33 |

| 2 | 11203 | 29 |

| 3 | 11212 | 23 |

| 4 | 11233 | 21 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| 159 | 11379 | 1 |

| 160 | 10007 | 1 |

| 161 | 10308 | 1 |

| 162 | 11362 | 1 |

| 163 | 11694 | 1 |

164 rows × 2 columns

A comprehensive list of ZIP codes by borough can be obtained, for example, from the New York City Department of Health’s UHF Codes. We can use this list to check the validity of the zip codes in the data.

# List of valid NYC ZIP codes compiled from UHF codes

# Define all_valid_zips based on the earlier extracted ZIP codes

all_valid_zips = {

10463, 10471, 10466, 10469, 10470, 10475, 10458, 10467, 10468,

10461, 10462, 10464, 10465, 10472, 10473, 10453, 10457, 10460,

10451, 10452, 10456, 10454, 10455, 10459, 10474, 11211, 11222,

11201, 11205, 11215, 11217, 11231, 11213, 11212, 11216, 11233,

11238, 11207, 11208, 11220, 11232, 11204, 11218, 11219, 11230,

11203, 11210, 11225, 11226, 11234, 11236, 11239, 11209, 11214,

11228, 11223, 11224, 11229, 11235, 11206, 11221, 11237, 10031,

10032, 10033, 10034, 10040, 10026, 10027, 10030, 10037, 10039,

10029, 10035, 10023, 10024, 10025, 10021, 10028, 10044, 10128,

10001, 10011, 10018, 10019, 10020, 10036, 10010, 10016, 10017,

10022, 10012, 10013, 10014, 10002, 10003, 10009, 10004, 10005,

10006, 10007, 10038, 10280, 11101, 11102, 11103, 11104, 11105,

11106, 11368, 11369, 11370, 11372, 11373, 11377, 11378, 11354,

11355, 11356, 11357, 11358, 11359, 11360, 11361, 11362, 11363,

11364, 11374, 11375, 11379, 11385, 11365, 11366, 11367, 11414,

11415, 11416, 11417, 11418, 11419, 11420, 11421, 11412, 11423,

11432, 11433, 11434, 11435, 11436, 11004, 11005, 11411, 11413,

11422, 11426, 11427, 11428, 11429, 11691, 11692, 11693, 11694,

11695, 11697, 10302, 10303, 10310, 10301, 10304, 10305, 10314,

10306, 10307, 10308, 10309, 10312

}

# Convert set to list of strings

all_valid_zips = list(map(str, all_valid_zips))

# Identify invalid ZIP codes (including NaN)

invalid_zips = df[

df['zip_code'].isna() | ~df['zip_code'].isin(all_valid_zips)

]['zip_code']

# Calculate frequency of invalid ZIP codes

invalid_zip_freq = invalid_zips.value_counts(dropna=False).reset_index()

invalid_zip_freq.columns = ['zip_code', 'frequency']

invalid_zip_freq| zip_code | frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | NaN | 284 |

| 1 | 10000 | 4 |

| 2 | 10065 | 3 |

| 3 | 10075 | 2 |

| 4 | 11430 | 1 |

As it turns out, the collection of valid NYC zip codes differ from different sources. From United States Zip Codes, 10065 appears to be a valid NYC zip code. Under this circumstance, it might be safer to not remove any zip code from the data.

To be safe, let’s concatenate valid and invalid zips.

# Convert invalid ZIP codes to a set of strings

invalid_zips_set = set(invalid_zip_freq['zip_code'].dropna().astype(str))

# Convert all_valid_zips to a set of strings (if not already)

valid_zips_set = set(map(str, all_valid_zips))

# Merge both sets

merged_zips = invalid_zips_set | valid_zips_set # Union of both setsAre missing in zip code and borough always co-occur?

# Check if missing values in 'zip_code' and 'borough' always co-occur

# Count rows where both are missing

missing_cooccur = df[['zip_code', 'borough']].isnull().all(axis=1).sum()

# Count total missing in 'zip_code' and 'borough', respectively

total_missing_zip_code = df['zip_code'].isnull().sum()

total_missing_borough = df['borough'].isnull().sum()

# If missing in both columns always co-occur, the number of missing

# co-occurrences should be equal to the total missing in either column

np.array([missing_cooccur, total_missing_zip_code, total_missing_borough])array([284, 284, 284])Are there cases where zip_code and borough are missing but the geo codes are not missing? If so, fill in zip_code and borough using the geo codes by reverse geocoding.

First make sure geopy is installed.

pip install geopyNow we use module Nominatim in package geopy to reverse geocode.

from geopy.geocoders import Nominatim

import time

# Initialize the geocoder; the `user_agent` is your identifier

# when using the service. Be mindful not to crash the server

# by unlimited number of queries, especially invalid code.

geolocator = Nominatim(user_agent="jyGeopyTry")We write a function to do the reverse geocoding given lattitude and longitude.

# Function to fill missing zip_code

def get_zip_code(latitude, longitude):

try:

location = geolocator.reverse((latitude, longitude), timeout=10)

if location:

address = location.raw['address']

zip_code = address.get('postcode', None)

return zip_code

else:

return None

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error: {e} for coordinates {latitude}, {longitude}")

return None

finally:

time.sleep(1) # Delay to avoid overwhelming the serviceLet’s try it out:

# Example usage

latitude = 40.730610

longitude = -73.935242

get_zip_code(latitude, longitude)'11101'The function get_zip_code can then be applied to rows where zip code is missing but geocodes are not to fill the missing zip code.

Once zip code is known, figuring out burough is simple because valid zip codes from each borough are known.

6.4 Accessing Census Data

The U.S. Census Bureau provides extensive demographic, economic, and social data through multiple surveys, including the decennial Census, the American Community Survey (ACS), and the Economic Census. These datasets offer valuable insights into population trends, economic conditions, and community characteristics at multiple geographic levels.

There are multiple ways to access Census data. For example:

- Census API: The Census API allows programmatic access to various datasets. It supports queries for different geographic levels and time periods.

- data.census.gov: The official web interface for searching and downloading Census data.

- IPUMS USA: Provides harmonized microdata for longitudinal research. Available at IPUMS USA.

- NHGIS: Offers historical Census data with geographic information. Visit NHGIS.

In addition, Python tools simplify API access and data retrieval.

6.4.1 Python Tools for Accessing Census Data

Several Python libraries facilitate Census data retrieval:

census: A high-level interface to the Census API, supporting ACS and decennial Census queries. Seecensuson PyPI.censusdis: Provides richer functionality: automatic discovery of variables, geographies, and datasets. Helpful if you don’t want to manually look up variable codes. Seecensusdison PyPI.us: Often used alongside census libraries to handle U.S. state and territory information (e.g., FIPS codes). Seeuson PyPI.

6.4.2 Zip-Code Level for NYC Crash Data

Now that we have NYC crash data, we might want to analyze patterns at the zip-code level to understand whether certain demographic or economic factors correlate with traffic incidents. While the crash dataset provides details about individual accidents, such as location, time, and severity, it does not contain contextual information about the neighborhoods where these crashes occur.

To perform meaningful zip-code-level analysis, we need additional data sources that provide relevant demographic, economic, and geographic variables. For example, understanding whether high-income areas experience fewer accidents, or whether population density influences crash frequency, requires integrating Census data. Key variables such as population size, median household income, employment rate, and population density can provide valuable context for interpreting crash trends across different zip codes.

Since the Census Bureau provides detailed estimates for these variables at the zip-code level, we can use the Census API or other tools to retrieve relevant data and merge it with the NYC crash dataset. To access the Census API, you need an API key, which is free and easy to obtain. Visit the Census API Request page and submit your email address to receive a key. Once you have the key, you must include it in your API requests to access Census data. The following demonstration assumes that you have registered, obtained your API key, and saved it in a file called censusAPIkey.txt.

# Import modules

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

import geopandas as gpd

from census import Census

from us import states

import os

import io

api_key = open("censusAPIkey.txt").read().strip()

c = Census(api_key)Suppose that we want to get some basic info from ACS data of the year of 2024 for all the NYC zip codes. The variable names can be found in the ACS variable documentation.

ACS_YEAR = 2024

ACS_DATASET = "acs/acs5"

# Important ACS variables (including land area for density calculation)

ACS_VARIABLES = {

"B01003_001E": "Total Population",

"B19013_001E": "Median Household Income",

"B02001_002E": "White Population",

"B02001_003E": "Black Population",

"B02001_005E": "Asian Population",

"B15003_022E": "Bachelor’s Degree Holders",

"B15003_025E": "Graduate Degree Holders",

"B23025_002E": "Labor Force",

"B23025_005E": "Unemployed",

"B25077_001E": "Median Home Value"

}

# Convert set to list of strings

merged_zips = list(map(str, merged_zips))Let’s set up the query to request the ACS data, and process the returned data.

acs_data = c.acs5.get(

list(ACS_VARIABLES.keys()),

{'for': f'zip code tabulation area:{",".join(merged_zips)}'}

)

# Convert to DataFrame

df_acs = pd.DataFrame(acs_data)

# Rename columns

df_acs.rename(columns=ACS_VARIABLES, inplace=True)

df_acs.rename(columns={"zip code tabulation area": "ZIP Code"}, inplace=True)We could save the ACS data df_acs in feather format (see next Section).

df_acs.to_feather("data/acs2023.feather")The population density could be an important factor for crash likelihood. To obtain the population densities, we need the areas of the zip codes. The shape files can be obtained from NYC Open Data.

import requests

import zipfile

import geopandas as gpd

# Define the NYC MODZCTA shapefile URL and extraction directory

shapefile_url = "https://data.cityofnewyork.us/api/geospatial/pri4-ifjk?method=export&format=Shapefile"

extract_dir = "tmp/MODZCTA_Shapefile"

# Create the directory if it doesn't exist

os.makedirs(extract_dir, exist_ok=True)

# Step 1: Download and extract the shapefile

print("Downloading MODZCTA shapefile...")

response = requests.get(shapefile_url)

with zipfile.ZipFile(io.BytesIO(response.content), "r") as z:

z.extractall(extract_dir)

print(f"Shapefile extracted to: {extract_dir}")Downloading MODZCTA shapefile...

Shapefile extracted to: tmp/MODZCTA_ShapefileNow we process the shape file to calculate the areas of the polygons.

# Step 2: Automatically detect the correct .shp file

shapefile_path = None

for file in os.listdir(extract_dir):

if file.endswith(".shp"):

shapefile_path = os.path.join(extract_dir, file)

break # Use the first .shp file found

if not shapefile_path:

raise FileNotFoundError("No .shp file found in extracted directory.")

print(f"Using shapefile: {shapefile_path}")

# Step 3: Load the shapefile into GeoPandas

gdf = gpd.read_file(shapefile_path)

# Step 4: Convert to CRS with meters for accurate area calculation

gdf = gdf.to_crs(epsg=3857)

# Step 5: Compute land area in square miles

gdf['land_area_sq_miles'] = gdf['geometry'].area / 2_589_988.11

# 1 square mile = 2,589,988.11 square meters

print(gdf[['modzcta', 'land_area_sq_miles']].head())Using shapefile: tmp/MODZCTA_Shapefile/geo_export_fc839ccd-10c1-440c-b689-2b3d894b1f7a.shp

modzcta land_area_sq_miles

0 10001 1.153516

1 10002 1.534509

2 10003 1.008318

3 10026 0.581848

4 10004 0.256876Let’s export this data frame for future usage in feather format (see next Section).

gdf[['modzcta', 'land_area_sq_miles']].to_feather('data/nyc_zip_areas.feather')Now we are ready to merge the two data frames.

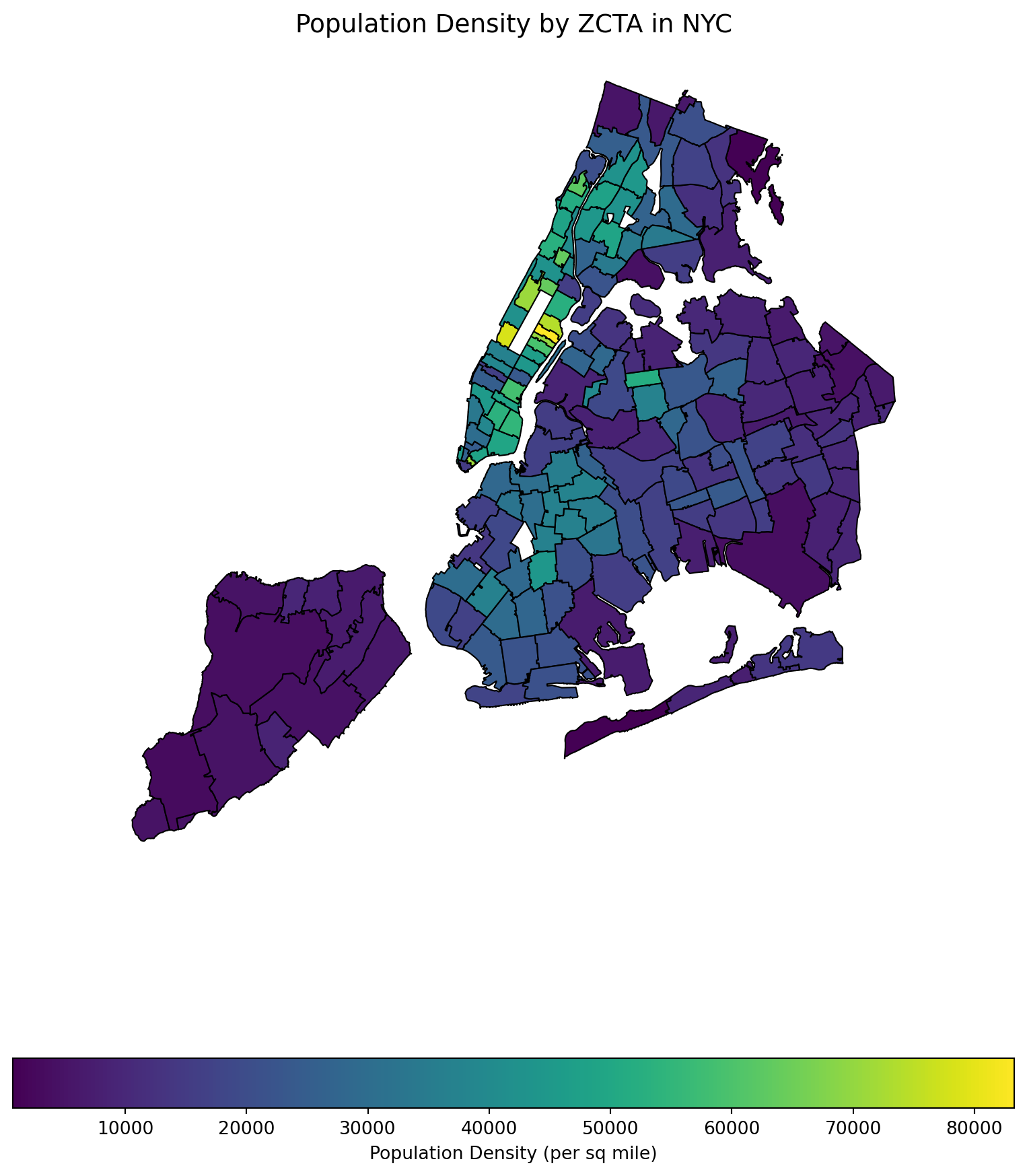

# Merge ACS data (`df_acs`) directly with MODZCTA land area (`gdf`)

gdf = gdf.merge(df_acs, left_on='modzcta', right_on='ZIP Code', how='left')

# Calculate Population Density (people per square mile)

gdf['popdensity_per_sq_mile'] = (

gdf['Total Population'] / gdf['land_area_sq_miles']

)

# Display first few rows

print(gdf[['modzcta', 'Total Population', 'land_area_sq_miles',

'popdensity_per_sq_mile']].head()) modzcta Total Population land_area_sq_miles popdensity_per_sq_mile

0 10001 29079.0 1.153516 25209.019713

1 10002 75517.0 1.534509 49212.471465

2 10003 53825.0 1.008318 53380.992071

3 10026 37113.0 0.581848 63784.749994

4 10004 3875.0 0.256876 15085.082190Some visualization of population density.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import geopandas as gpd

# Set up figure and axis

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 12))

# Plot the choropleth map

gdf.plot(column='popdensity_per_sq_mile',

cmap='viridis', # Use a visually appealing color map

linewidth=0.8,

edgecolor='black',

legend=True,

legend_kwds={'label': "Population Density (per sq mile)",

'orientation': "horizontal"},

ax=ax)

# Add a title

ax.set_title("Population Density by ZCTA in NYC", fontsize=14)

# Remove axes

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_frame_on(False)

# Show the plot

plt.show()

6.5 Cross-platform Data Format Arrow

The CSV format (and related formats like TSV - tab-separated values) for data tables is ubiquitous, convenient, and can be read or written by many different data analysis environments, including spreadsheets. An advantage of the textual representation of the data in a CSV file is that the entire data table, or portions of it, can be previewed in a text editor. However, the textual representation can be ambiguous and inconsistent. The format of a particular column: Boolean, integer, floating-point, text, factor, etc. must be inferred from text representation, often at the expense of reading the entire file before these inferences can be made. Experienced data scientists are aware that a substantial part of an analysis or report generation is often the “data cleaning” involved in preparing the data for analysis. This can be an open-ended task — it required numerous trial-and-error iterations to create the list of different missing data representations we use for the sample CSV file and even now we are not sure we have them all.

To read and export data efficiently, leveraging the Apache Arrow library can significantly improve performance and storage efficiency, especially with large datasets. The IPC (Inter-Process Communication) file format in the context of Apache Arrow is a key component for efficiently sharing data between different processes, potentially written in different programming languages. Arrow’s IPC mechanism is designed around two main file formats:

- Stream Format: For sending an arbitrary length sequence of Arrow record batches (tables). The stream format is useful for real-time data exchange where the size of the data is not known upfront and can grow indefinitely.

- File (or Feather) Format: Optimized for storage and memory-mapped access, allowing for fast random access to different sections of the data. This format is ideal for scenarios where the entire dataset is available upfront and can be stored in a file system for repeated reads and writes.

Apache Arrow provides a columnar memory format for flat and hierarchical data, optimized for efficient data analytics. It can be used in Python through the pyarrow package. Here’s how you can use Arrow to read, manipulate, and export data, including a demonstration of storage savings.

First, ensure you have pyarrow installed on your computer (and preferrably, in your current virtual environment):

pip install pyarrowFeather is a fast, lightweight, and easy-to-use binary file format for storing data frames, optimized for speed and efficiency, particularly for IPC and data sharing between Python and R or Julia.

The following code processes the raw data in CSV format and write out in Arrow format.

# File paths

csv_file = 'data/nyc_crashes_lbdwk_2025.csv'

feather_file = 'tmp/nyc_crashes_lbdwk_2025.feather'

import pandas as pd

# Move 'crash_datetime' to the first column

df = df[['crash_datetime'] + df.drop(columns=['crash_datetime']).columns.tolist()]

df['zip_code'] = df['zip_code'].astype(str).str.rstrip('.0')

df = df.sort_values(by='crash_datetime')

df.to_feather(feather_file)Let’s compare the file sizes of the feather format and the CSV format.

import os

# Get file sizes in bytes

csv_size = os.path.getsize(csv_file)

feather_size = os.path.getsize(feather_file)

# Convert bytes to a more readable format (e.g., MB)

csv_size_mb = csv_size / (1024 * 1024)

feather_size_mb = feather_size / (1024 * 1024)

# Print the file sizes

print(f"CSV file size: {csv_size_mb:.2f} MB")

print(f"Feather file size: {feather_size_mb:.2f} MB")CSV file size: 0.27 MB

Feather file size: 0.13 MBRead the feather file back in:

#| eval: false

dff = pd.read_feather(feather_file)

dff.shape6.6 Database operation with SQL

This section was prepared by Lewis Milun.

6.6.1 Introduction

Structured Query Language (SQL) is one of the standard languages that is used to work with large databases. It uses tables to store and display data, creating an organized and comprehensible interface that makes it far easier to track and view your data.

Some advantages of using SQL include its ability to handle large amounts of data while simultaneously simplifying the process of creating, updating, and retrieving any data you may want.

The biggest advantage of using SQL for the purposes of this class is that it can very easily connect with Python and R. This makes it so that we can have all of the benefits of working with SQL while still working in the Python environment we already have set up.

6.6.2 Setting up Databases

In this section, we will be working with two databases, one that’s built into a Python package (nycflights13) and one that we used for our midterm project (311 Service Requests)

6.6.2.1 nycflights13

This database uses the pandas package and includes flight data for all flights that left New York City airports in 2013. The database includes several tables including ones that detail each flight, airline, airport, and much more info regarding the flights. The data in this database is contained across several tables. Data stored like this would typically be irritating to deal with however it is proven simple when working with SQL.

To set up this database, we need to import the proper packages:

import sqlite3

import pandas as pd

from nycflights13 import flights, airlines, airportsHere we imported “sqlite3” which is the package to import when working with SQL. We also imported “pandas” which also includes the nycflights13 database and from there imported the three tables we will be working with.

Now, we want to establish the connection between Python and our SQL database:

nycconn = sqlite3.connect("nycflights13.db")This snippet both creates the nycflights13.db database and establishes nycconn as our connection to this database.

Next step is to add the three tables we imported from nycflights13 to the database:

flights.to_sql("flights", nycconn, if_exists="replace", index=False)

airlines.to_sql("airlines", nycconn, if_exists="replace", index=False)

airports.to_sql("airports", nycconn, if_exists="replace", index=False)What this does is converts the three pandas dataframes into tables in the SQL database. The if_exists argument handles what would happen if there is already a table in the database with the same name. The index argument is determining whether or not the first column of the dataframe should be handled as the index of the table in the dataframe.

6.6.2.2 serviceRequests Database

First, we need to import our serviceRequests data from the csv in the data folder:

df = pd.read_csv("data/serviceRequests06-09-2025_07-05-2025.csv")Now we need to repeat the process from nycflights13 but for our serviceRequests:

srconn = sqlite3.connect("serviceRequests.db")

df.to_sql("requests", srconn, if_exists="replace", index=False)Here we imported the dataframe we got from the csv file as the only table in the serviceRequests.db database.

6.6.3 Query Basics

Now we can move onto working with the data in our SQL databases. The most common use for SQL is writing a “query” which is a statement sent to the SQL database that returns a selection of rows and columns from the tables in a database.

We will be looking at the “flights” table in our nycflights13 database for this section.

6.6.3.1 SELECT and FROM

The following is the most basic possible query one can perform:

query = """

SELECT *

FROM flights;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| year | month | day | dep_time | sched_dep_time | dep_delay | arr_time | sched_arr_time | arr_delay | carrier | flight | tailnum | origin | dest | air_time | distance | hour | minute | time_hour | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 517.0 | 515 | 2.0 | 830.0 | 819 | 11.0 | UA | 1545 | N14228 | EWR | IAH | 227.0 | 1400 | 5 | 15 | 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z |

| 1 | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 533.0 | 529 | 4.0 | 850.0 | 830 | 20.0 | UA | 1714 | N24211 | LGA | IAH | 227.0 | 1416 | 5 | 29 | 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z |

| 2 | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 542.0 | 540 | 2.0 | 923.0 | 850 | 33.0 | AA | 1141 | N619AA | JFK | MIA | 160.0 | 1089 | 5 | 40 | 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z |

| 3 | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 544.0 | 545 | -1.0 | 1004.0 | 1022 | -18.0 | B6 | 725 | N804JB | JFK | BQN | 183.0 | 1576 | 5 | 45 | 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z |

| 4 | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 554.0 | 600 | -6.0 | 812.0 | 837 | -25.0 | DL | 461 | N668DN | LGA | ATL | 116.0 | 762 | 6 | 0 | 2013-01-01T11:00:00Z |

This snippet represents the basic form of writing SQL queries in Python. We create a variable ‘query’ that contains the statement we intend to pass into SQL. The last line then uses the nycconn connection we created earlier to pass our query into SQL and it returns the head() of the result we get back.

This query is the most basic query, as it returns the entire flights table. The SELECT line of the query is where you put the names of which columns you want from your table. You specify which table you want to work with on the FROM line. We put “*” in our SELECT line which returns all columns. All SQL queries must end with “;”, otherwise you’ll get an error.

Now let’s try to simplify what we’re seeing by only looking at the origins and destinations of the flights:

query = """

SELECT origin, dest

FROM flights;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | EWR | IAH |

| 1 | LGA | IAH |

| 2 | JFK | MIA |

| 3 | JFK | BQN |

| 4 | LGA | ATL |

Here we replaced the “*” in our SELECT statement with “origin, dest” This told SQL to only return those two columns from the database.

6.6.3.2 ORDER BY

These columns are quite messy to look at so let’s try sorting them by origin:

query = """

SELECT origin, dest

FROM flights

ORDER BY origin;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | EWR | IAH |

| 1 | EWR | ORD |

| 2 | EWR | FLL |

| 3 | EWR | SFO |

| 4 | EWR | LAS |

Here we added a new “ORDER BY” line. This line tells SQL what columns to sort the list by.

You can sort by multiple columns just by listing them with commas in between:

query = """

SELECT origin, dest

FROM flights

ORDER BY origin, dest;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | EWR | ALB |

| 1 | EWR | ALB |

| 2 | EWR | ALB |

| 3 | EWR | ALB |

| 4 | EWR | ALB |

6.6.3.3 SELECT DISTINCT

Now that the list is properly sorted, we can see that there are multiple flights from each origin to destination combination. If we want to only see the unique columns, we can do this:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT origin, dest

FROM flights

ORDER BY origin, dest;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | EWR | ALB |

| 1 | EWR | ANC |

| 2 | EWR | ATL |

| 3 | EWR | AUS |

| 4 | EWR | AVL |

Here we replaced our “SELECT” statement with a “SELECT DISTINCT” statement. This tells SQL to only return the unique columns from the query.

6.6.4 Conditionals

Usually you wouldn’t want to just return all rows or all unique rows from a table You instead will have conditions that determine which rows are relevant to your query

6.6.4.1 WHERE

The way you can add conditionals to your query is by adding a “WHERE” line. Let’s take the same list from the last section and filter it so that only the flights that departed from LGA are returned:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT origin, dest

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LGA'

ORDER BY origin, dest;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | LGA | ATL |

| 1 | LGA | AVL |

| 2 | LGA | BGR |

| 3 | LGA | BHM |

| 4 | LGA | BNA |

You add conditionals in the “WHERE” line by using the following comparators:

- ‘=’

- ‘<’

- ‘>’

- ‘<=’

- ‘>=’

- ‘!=’

Be careful of the type of the data in a particular column!

6.6.4.2 AND, OR, and NOT

You can add multiple conditionals by using AND, OR, and parentheses

query = """

SELECT origin, dest

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LGA' AND dest = 'ATL'

ORDER BY origin, dest;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | LGA | ATL |

| 1 | LGA | ATL |

| 2 | LGA | ATL |

| 3 | LGA | ATL |

| 4 | LGA | ATL |

This uses AND to return all flights that departed from LGA and arrived in ATL

We can also use OR to return all flights that either departed from LGA or arrived in ATL:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT origin, dest

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LGA' OR dest = 'ATL'

ORDER BY origin, dest;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | EWR | ATL |

| 1 | JFK | ATL |

| 2 | LGA | ATL |

| 3 | LGA | AVL |

| 4 | LGA | BGR |

When you want to get more complicated with your conditionals, parenthesis can be used to ensure SQL is correctly mixing the AND and OR statements.

Use NOT to return the opposite of a statement:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT origin, dest

FROM flights

WHERE NOT (origin = 'LGA' OR dest = 'ATL')

ORDER BY origin, dest;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | EWR | ALB |

| 1 | EWR | ANC |

| 2 | EWR | AUS |

| 3 | EWR | AVL |

| 4 | EWR | BDL |

6.6.4.3 COUNT

An easy way in SQL to see the total number of rows that fit the conditions you’ve specified:

query = """

SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT dest)

FROM flights

WHERE NOT (origin = 'LGA' OR dest = 'ATL');

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| COUNT(DISTINCT dest) | |

|---|---|

| 0 | 97 |

This returns the number of distinct destinations that fit the specified criteria

6.6.4.4 LIMIT

If you don’t want to use .head() to only display the first few rows, this can be done in SQL using a LIMIT statement:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT carrier, origin, dest

FROM flights

WHERE carrier = 'UA'

ORDER BY origin, dest

LIMIT 5;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn)| carrier | origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | UA | EWR | ANC |

| 1 | UA | EWR | ATL |

| 2 | UA | EWR | AUS |

| 3 | UA | EWR | BDL |

| 4 | UA | EWR | BOS |

This query added the “carrier” column that displays the airline that held the flight. We specified that we want all flights from the “UA” airline and limited the result to 5 rows.

An interesting thing you can do with conditionals in SQL is to filter by values in a column that you are not displaying:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT origin, dest

FROM flights

WHERE carrier = 'UA'

ORDER BY origin, dest

LIMIT 5;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn)| origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | EWR | ANC |

| 1 | EWR | ATL |

| 2 | EWR | AUS |

| 3 | EWR | BDL |

| 4 | EWR | BOS |

Here we still filter by flights from the “UA” airline but we don’t display the column as that would be very redundant.

6.6.5 Joins

The last query that we did was useful, however it isn’t realistic to expect users to memorize the two-digit codes for all airlines. Thankfully, there is the airlines table in our nycflights13.db database. Let’s take a look at it:

query = """

SELECT *

FROM airlines;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| carrier | name | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 9E | Endeavor Air Inc. |

| 1 | AA | American Airlines Inc. |

| 2 | AS | Alaska Airlines Inc. |

| 3 | B6 | JetBlue Airways |

| 4 | DL | Delta Air Lines Inc. |

This table is much simpler than the “flights” table as it only has two columns.

6.6.5.1 INNER JOIN

Logically, we wouldn’t want our outputted table to display the two-digit code that represents each airline but instead we’d want to see the name of the airline. Thankfully, SQL has a way to join the data from the two tables together:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT a.name AS airline_name, f.origin, f.dest

FROM flights AS f

INNER JOIN airlines AS a

ON f.carrier = a.carrier;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| airline_name | origin | dest | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | United Air Lines Inc. | EWR | IAH |

| 1 | United Air Lines Inc. | LGA | IAH |

| 2 | American Airlines Inc. | JFK | MIA |

| 3 | JetBlue Airways | JFK | BQN |

| 4 | Delta Air Lines Inc. | LGA | ATL |

This is a much more complicated query that returns a table of the distinct airline, origin, and destination in the flights database. We introduced three new statements in this query:

AS is similar to how “as” is used when importing packages in Python. It gives us an opportunity to use a shorthand instead of needing to type out the full table names every time we mention a column. It can also be used in our SELECT line to name columns in our resultant table

INNER JOIN connects a new table to our query (in this case, the new table is airlines).

ON lets SQL know what column in each table it should use to connect the tables. Here we told SQL that in every row, when it reaches the carrier column in flights, it should use that as its reference for what row in airlines to use for values in this row. For example, in the first row, SQL saw that the carrier name in flights was “UA”. SQL then looked in the carrier column in airlines and found the row in which “UA” was the value in that table’s carrier column. So when SQL was calculating the value for airline_name in the first row, it knew which column to search in airline to find “United Air Lines Inc.”

JOIN statements are key when using SQL to display data. This is what allows SQL databases to be in such nice and concise structures.

Now let’s also add in the values from the “airports” table so that we get the full names of the airports instead of their three-digit codes:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT a.name AS airline_name,

orig.name AS origin_name,

dest.name AS dest_name

FROM flights AS f

INNER JOIN airlines AS a

ON f.carrier = a.carrier

INNER JOIN airports AS orig

ON f.origin = orig.faa

INNER JOIN airports AS dest

ON f.dest = dest.faa;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| airline_name | origin_name | dest_name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | United Air Lines Inc. | Newark Liberty Intl | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 1 | United Air Lines Inc. | La Guardia | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 2 | American Airlines Inc. | John F Kennedy Intl | Miami Intl |

| 3 | Delta Air Lines Inc. | La Guardia | Hartsfield Jackson Atlanta Intl |

| 4 | United Air Lines Inc. | Newark Liberty Intl | Chicago Ohare Intl |

Here we use three different INNER JOIN statements to connect the three tables properly. The reason we use two JOIN statements to connect the same “airports” table is to have SQL be able to look separately for the origin and destination airport names. This query also utilizes indenting to make the query far more readable.

6.6.5.2 The difference between the three JOINs

SQL has three different versions of JOIN statements: + INNER JOIN + LEFT JOIN + RIGHT JOIN

This allows the user to determine what rows get included as a result of joining two tables. Let’s take a look at the differences:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT f.flight,

a.name AS airline_name,

orig.name AS origin_name,

dest.name AS dest_name

FROM flights AS f

INNER JOIN airlines AS a

ON f.carrier = a.carrier

INNER JOIN airports AS orig

ON f.origin = orig.faa

INNER JOIN airports AS dest

ON f.dest = dest.faa;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| flight | airline_name | origin_name | dest_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1545 | United Air Lines Inc. | Newark Liberty Intl | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 1 | 1714 | United Air Lines Inc. | La Guardia | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 2 | 1141 | American Airlines Inc. | John F Kennedy Intl | Miami Intl |

| 3 | 461 | Delta Air Lines Inc. | La Guardia | Hartsfield Jackson Atlanta Intl |

| 4 | 1696 | United Air Lines Inc. | Newark Liberty Intl | Chicago Ohare Intl |

INNER JOIN is the most common. This is because the result will only include rows in which the values in question are included in both tables. For example, if there was a row in flights that included an airline code that was not present in airlines, then SQL will not include that row in the result.

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT f.flight,

a.name AS airline_name,

orig.name AS origin_name,

dest.name AS dest_name

FROM flights AS f

LEFT JOIN airlines AS a

ON f.carrier = a.carrier

LEFT JOIN airports AS orig

ON f.origin = orig.faa

LEFT JOIN airports AS dest

ON f.dest = dest.faa;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn).head()| flight | airline_name | origin_name | dest_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1545 | United Air Lines Inc. | Newark Liberty Intl | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 1 | 1714 | United Air Lines Inc. | La Guardia | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 2 | 1141 | American Airlines Inc. | John F Kennedy Intl | Miami Intl |

| 3 | 725 | JetBlue Airways | John F Kennedy Intl | None |

| 4 | 461 | Delta Air Lines Inc. | La Guardia | Hartsfield Jackson Atlanta Intl |

LEFT JOIN will return all rows that are in flights regardless of if SQL was able to find matching rows on the other tables. This is perfectly represented in the fourth row of the output. On flights, the destination for flight 725 is “BQN” which is not an airport on the airports table. If you look back to the result of the INNER JOIN, this row was removed from the result however it is present here because we used flights as our only reference for rows and therefore the row is included but the destination name is left as “None”

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT f.flight,

f.origin,

dest.name AS dest_name

FROM flights AS f

RIGHT JOIN airports AS dest

ON f.dest = dest.faa;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, nycconn)| flight | origin | dest_name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1545.0 | EWR | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 1 | 1714.0 | LGA | George Bush Intercontinental |

| 2 | 1141.0 | JFK | Miami Intl |

| 3 | 461.0 | LGA | Hartsfield Jackson Atlanta Intl |

| 4 | 1696.0 | EWR | Chicago Ohare Intl |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 13275 | NaN | None | Boston Back Bay Station |

| 13276 | NaN | None | Black Rock |

| 13277 | NaN | None | New Haven Rail Station |

| 13278 | NaN | None | Wilmington Amtrak Station |

| 13279 | NaN | None | Washington Union Station |

13280 rows × 3 columns

RIGHT JOIN is basically the opposite of LEFT JOIN. Instead of using flights as its basis for what rows to include, RIGHT JOIN uses the joined tables instead. As you can see, the fourth row is being skipped again because the airports table is being used as reference instead. Also, the table ends with rows for all destinations from the airports table. SQL includes them because it is looking for all rows that include destinations from the airports table. This includes all rows from the airports table itself.

6.6.6 Creating Tables

Let’s take a look at our serviceRequests.db’s requests table:

query = """

SELECT *

FROM requests;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, srconn).head()| Unique Key | Created Date | Closed Date | Agency | Agency Name | Complaint Type | Descriptor | Location Type | Incident Zip | Incident Address | ... | Vehicle Type | Taxi Company Borough | Taxi Pick Up Location | Bridge Highway Name | Bridge Highway Direction | Road Ramp | Bridge Highway Segment | Latitude | Longitude | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 65477840 | 07/05/2025 11:59:51 AM | None | EDC | Economic Development Corporation | Noise - Helicopter | Other | Above Address | 11414.0 | 88-12 151 AVENUE | ... | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | 40.668478 | -73.846874 | (40.6684777987759, -73.84687384879807) |

| 1 | 65473303 | 07/05/2025 11:59:38 AM | 07/05/2025 12:53:29 PM | NYPD | New York City Police Department | Blocked Driveway | Partial Access | Street/Sidewalk | 11207.0 | 737 CHAUNCEY STREET | ... | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | 40.685343 | -73.907410 | (40.685343220141434, -73.90741025722555) |

| 2 | 65479182 | 07/05/2025 11:59:30 AM | 07/05/2025 07:24:47 PM | DHS | Department of Homeless Services | Homeless Person Assistance | Chronic | Store/Commercial | 10014.0 | 11 LITTLE WEST 12 STREET | ... | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | 40.739795 | -74.006708 | (40.739795176046364, -74.00670839867178) |

| 3 | 65472680 | 07/05/2025 11:59:27 AM | 07/05/2025 02:28:38 PM | NYPD | New York City Police Department | Abandoned Vehicle | With License Plate | Street/Sidewalk | 10039.0 | 2743 FREDERICK DOUGLASS BOULEVARD | ... | Car | None | None | None | None | None | None | 40.823646 | -73.941340 | (40.82364581471349, -73.94134045287531) |

| 4 | 65479165 | 07/05/2025 11:59:20 AM | 07/06/2025 01:13:50 AM | NYPD | New York City Police Department | Encampment | None | Residential Building/House | 10456.0 | 1398 GRAND CONCOURSE | ... | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | 40.838557 | -73.913883 | (40.83855707927812, -73.91388286014495) |

5 rows × 41 columns

This table is incredibly complicated and redundant through repeated information such as each row having both “Agency” and “Agency Name”. This redundancy clutters the table, making it difficult to read. It would be much better if the database wasn’t just one table and instead was formatted like the nycflights13.db

Take note that we have begun using our other connection (srconn instead of nycconn) because we are working with our other database.

Thankfully, SQL makes it very simple to create new tables from the results of a query. Looking back at the redundancy with agencies, we can create the following query to see all the agency codes and their corresponding names:

query = """

SELECT DISTINCT Agency, "Agency Name"

FROM requests

ORDER BY Agency;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, srconn).head()| Agency | Agency Name | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | DCWP | Department of Consumer and Worker Protection |

| 1 | DEP | Department of Environmental Protection |

| 2 | DHS | Department of Homeless Services |

| 3 | DOB | Department of Buildings |

| 4 | DOE | Department of Education |

Something to note here is how one can handle a column name that includes a space or a comma. If you put the name of the column in quotes, then SQL will handle everything inside the quotes as the name of the column.

Now that we have created this query, we can make the result into its own table in the database:

query = """

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS agencies AS

SELECT DISTINCT Agency, "Agency Name"

FROM requests

ORDER BY Agency;

"""

srconn.execute(query)

srconn.commit()There are a few key parts to this query:

Firstly, we have the first line which tells SQL to create a table named agencies and the AS works here to tell SQL to make the table be the result of the query that follows the first line.

Second, there is the statement “IF NOT EXISTS”. This is incredibly useful to include in the query as it ensures that you do not override any tables that you have previously made.

Lastly, we use different commands outside of creating the query variable. Instead of pd.read_sql_query(query, srconn), we have our connection to SQL execute the query we created, then commit the changes to the database.

Now that we have added the table to our database, we can query it:

query = """

SELECT *

FROM agencies;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, srconn).head()| Agency | Agency Name | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | DCWP | Department of Consumer and Worker Protection |

| 1 | DEP | Department of Environmental Protection |

| 2 | DHS | Department of Homeless Services |

| 3 | DOB | Department of Buildings |

| 4 | DOE | Department of Education |

This process can be repeated to clean up messy tables and messy databases.

6.6.7 Statement Order

Statements in a SQL query must go in a certain order, otherwise the query will return an error. The order is as follows:

- SELECT

- FROM

- JOIN

- WHERE

- GROUP BY

- HAVING

- ORDER BY

- LIMIT/OFFSET

6.6.8 Conclusion

SQL makes working with large datasets much easier by organizing databases and simplifying the process of displaying data. Using either the queries shown here as well as much more complicated queries, one can turn complex tables into databases that don’t unnecessarily repeat data, and that consist of easily read tables.

6.6.9 Further Readings

- W3 Schools SQL Tutorial

- [SQLite Tutorial (installing SQLite not necessary)] (https://www.sqlitetutorial.net/)